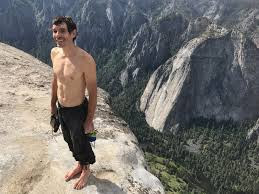

Honnolding

honnolding. verb. to stand in some high, precarious place with your back to the wall, looking straight into the abyss.

On Saturday 3rd June, Alex Honnold woke at dawn, pulled on his favourite red tee-shirt and cut-off trousers, ate his usual breakfast of oats and blueberries, and drove the van that serves as his home to El Capitan meadow.

Parking up, he hiked to the base of El Capitan - an iconic 3000 foot granite wall in Yosemite National Park, put on his climbing shoes and attached a small chalk bag around his waist.

At 5.32am, he found his first toe hold and began climbing. 3 hours and 56 minutes later, he reached the top. In a feat which most in the climbing world thought impossible, he had 'free solo'ed' the wall, using no ropes or safety equipment of any kind.

Already, this completion is being hailed as the greatest climb in the history of the sport. Tommy Caldwell, a climbing legend who made history with his ascent of El Capitan's Dawn Wall in 2015, was quoted as saying, 'This is the 'moon landing' of free solo.'

To specialise in free solo climbing, where one false move means certain death, is not for everyone. It appears that Alex Honnold does not experience fear like the rest of us.

Or maybe he does. Just sometimes.

In September 2008, a 23 year old Honnold was on the verge of an unprecedented achievement. After 2 hours of free solo climbing he was nine-tenths of the way up the north-west face of Half Dome, a 2000 foot wall, again in Yosemite. He had reached the Thank God Ledge - a precarious ramp on the wall's surface that varies in width from 5 to 12 inches along its length.

Reaching the ledge, fully-roped climbers usually hand-traverse left, facing the wall. Honnold had different ideas. He wanted to cross on his feet, with his back to the wall. The purest of styles. 'It was a matter of pride,' he wrote later.

Pulling himself onto the ledge, he put all his weight on one foothold, stood up, turned around and faced out. The wall at his back, overhanging a little, threatened to push him off balance.

Honnold observed later:

'The first few steps were completely normal, as if I was walking on a narrow sidewalk in the sky. But once it narrowed, I found myself inching along with my body glued to the wall, shuffling my feet and maintaining perfect body posture. I could have looked down and seen my pack sitting at the base of the route, but it would have pitched me head first off the wall.'

Alex Honnold almost never looses his cool. But a few minutes after traversing the Thank God Ledge, he experienced something new. He froze, questions like, 'What am I doing?' racing through his mind. Then he freaked out. And as Honnold knew full well, 'The minute you freak out, you're screwed.'

Honnold would describe the next five minutes as a 'very private hell.' But after that time, he eventually turned back to face the wall. He took his next move, his feet poised on smears of granite, his fingertips barely finding purchase on tiny wrinkles in the stone. And then a second wave of freak-out hit him. His calves cramped. If he didn't make the next move soon, he knew he would die. He was running out of time.

That next move was critical. To make it, Honnold had to plant his right foot on a smooth patch of stone, then step up and reach for a sharp-cut edge of rock that would hold his weight. He hesitated. He couldn't do it. An eternity passed. Then, he took a deep breath and went for it.

Minutes later, Honnold pulled himself onto the summit. A crowd of hikers chatted on, not paying him any attention at all, unaware of the feat he had just accomplished. He stood for a while, silent, looking out over Yosemite. Then, reaching down, he unlaced his shoes and began walking barefoot down the trail.

The only thing inevitable in life is change.

And yet, most of us fight against it all the time. We dye our hair. We subject ourselves to plastic surgery. We stick to the same hobbies. Do the same job for a lifetime even though it bores us to tears. We find comfort in the thought of stability, of standing still.

Inertia is an incredibly powerful force.

The reason we resist change is fear.

Things staying the same is easy. Embracing change is scary. But to live an authentic, satisfying life, embracing change is a necessity.

I like saying ,'Yes', even though I often find it difficult. When friends ask for advice - they're thinking of doing this or that, but they're not sure if things will work out, I'll inevitably reply, 'Yeah - go for it!' We're a resilient species. If we're faced with a sink or swim scenario, we'll usually swim - somehow.

I'm not keen on putting myself willingly out of my comfort zone. But it's something I consciously do more often nowadays, because I know it's good for me. It helps me grow. It makes me better. At times like this - stood on the ledge, looking out - I know it's important that I face my unease, stare down my resistance, and then - just like Alex - turn back to the wall and continue climbing.

Maybe the authentic, satisfying life we seek is achieved when we reach a time when we find ourselves in a job we love, doing things we love, mixing with people we love. A life where we accept some change- aging, death etc, but have no desire to actively seek change.

ReplyDelete